Chinese doctors have made a groundbreaking advancement in organ transplantation, successfully transplanting a liver from a genetically modified pig into a brain-dead human for the first time. This remarkable achievement raises hopes for a potential life-saving donor option in the future for patients in need of liver transplants.

Pigs have long been considered ideal candidates for organ donation, with several patients in the United States receiving pig kidneys and hearts in recent years. However, liver transplants have proven more challenging, and until now, no pig liver had been tested in a human body.

The global demand for liver donations continues to grow, and researchers believe gene-edited pigs could provide temporary relief to patients awaiting a human donor. The breakthrough took place at the Fourth Military Medical University in Xi’an, China, and the findings were published in the journal Nature.

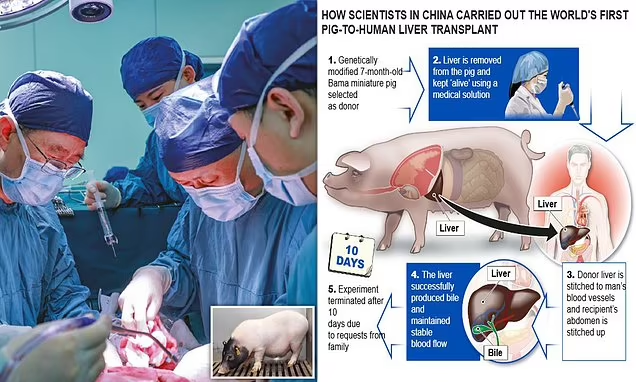

On March 10, 2024, a liver from a miniature pig, genetically modified with six altered genes to enhance its suitability as a donor, was transplanted into a brain-dead adult at the hospital. The trial was terminated after 10 days at the request of the family, with the doctors adhering to strict ethical guidelines.

The patient still retained their original liver and received what is known as an auxiliary transplant, where the pig liver functions as a “bridge organ,” supporting the patient’s existing liver while they wait for a human donor. During the 10-day observation period, the doctors monitored the liver’s blood flow, bile production, immune response, and other key functions.

According to Lin Wang, a co-author of the study, the pig liver “functioned really well” and successfully produced bile and the key protein albumin, demonstrating its potential for future use. “It’s a great achievement that could help people with liver problems in the future,” Lin said during a press conference.

Despite the promising results, experts caution that further research is necessary. Livers are complex organs that perform multiple vital functions, such as filtering the blood, breaking down substances like drugs and alcohol, and producing bile to remove waste and process fats. Although the pig liver showed functionality, it produced smaller amounts of bile and albumin compared to a human liver.

Lin emphasized that more research, including longer observation periods, is required to determine whether pig livers could replace human livers. The next step will involve testing the gene-edited pig liver in a living human.

Professor Peter Friend, a transplantation expert at Oxford University, called the results “valuable and impressive.” However, he noted, “this is not a replacement for liver transplantation from human donors (at least in the near term).” He pointed out that this research serves as a test for the compatibility of genetically modified livers with humans and could ultimately provide support for patients experiencing liver failure.

Lin also acknowledged the crucial role of US researchers in advancing this field. “We have learned quite a lot from the research performed and investigated by the United States doctors,” he said.

Last year, scientists at the University of Pennsylvania attached a pig liver to a brain-dead patient outside the body, but the organ was not transplanted. Additionally, while two US patients who received pig heart transplants have passed away, Towana Looney, 53, is recovering at home in Alabama after receiving a pig kidney transplant in November 2024.

This research marks an important milestone in the field of xenotransplantation, offering hope for the future of organ donation. As further studies are conducted, genetically modified pig organs could one day provide a vital solution for patients in desperate need of transplants, though challenges remain in perfecting their compatibility with human bodies.